Vendors in floating markets in Mekong Delta struggle to stay afloat as new roads and embankments push them to the brink.

By Mai Kieu

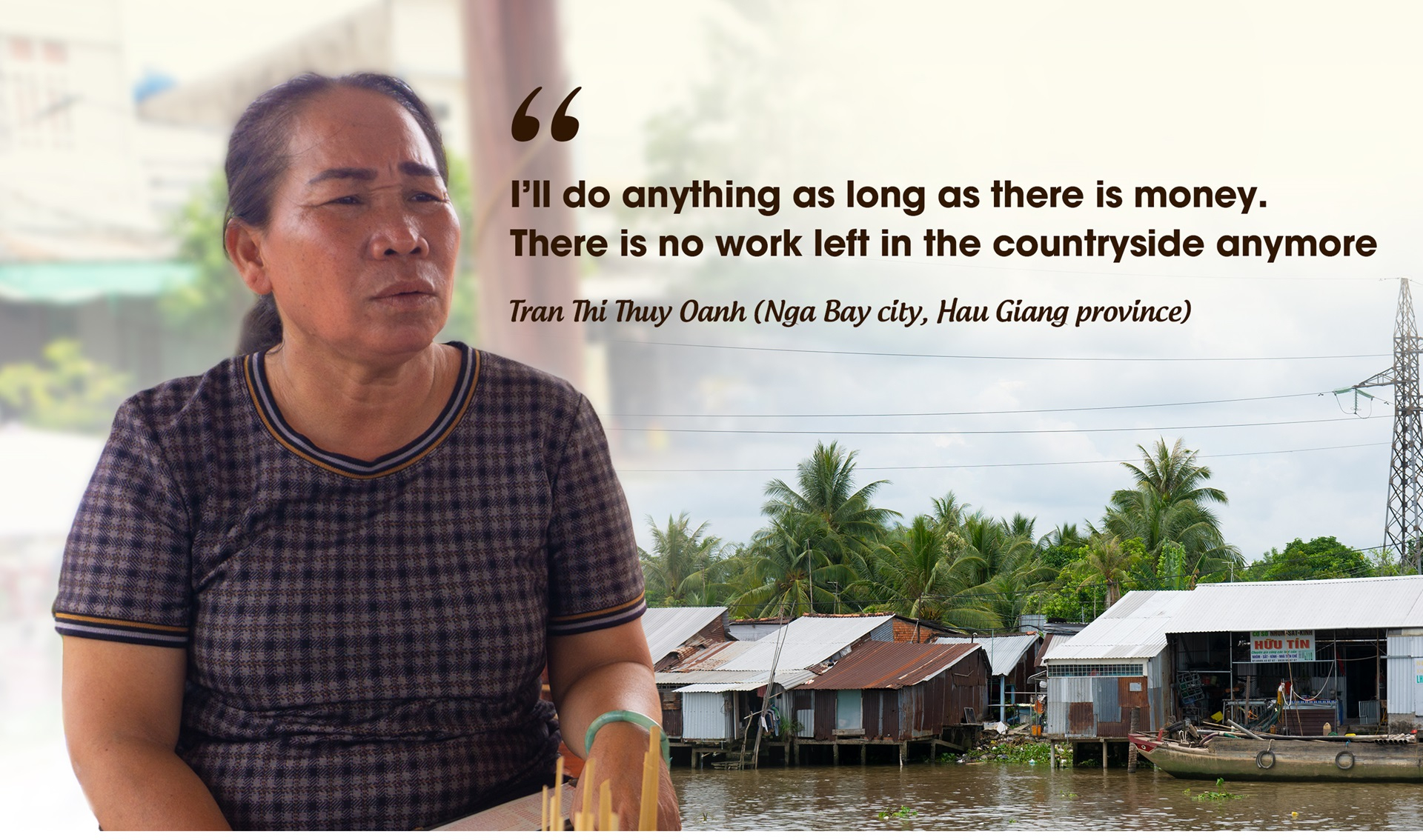

Clutching a large suitcase to her chest, Tran Thi Thuy Oanh gazed at Ho Chi Minh City’s bustling streets, and braced for a new life ahead.

This was not the first time she had migrated to the city. Oanh was originally from Nga Bay, once among the most vibrant floating markets in Mekong Delta. As a vendor, she earned a decent living – enough to support her six younger siblings until the early 2000s.

But then the market was relocated and her business started to dwindle.

Oanh had worked in Ho Chi Minh City for three years as a caregiver, then quickly returned home to raise her teenage son. She was determined to stay close to home, even if it meant scraping by weaving baskets and selling beverages.

This year, she decided to head to the city again. “I’ll do anything – housekeeping, childcare or manual labor – as long as there is money. There is no work left in the countryside anymore,” she lamented.

Over the past two decades, floating markets in Mekong Delta, once key cultural, transport and economic hubs, have been shrinking – leaving many residents like Oanh high and dry.

Inland waterway transportation is the key to the Ministry of Transport’s strategy for the Mekong Delta region through to 2030. A shift to inland freight transport is also significant in contributing to greenhouse gas emission reductions, according to the World Bank.

Yet recent infrastructure developments and culture-focused preservation efforts have not been able to slow the shrinking of these markets.

A bygone heyda of floating markets in Mekong Delta

The impacts of infrastructure development are evident in Cai Rang, the largest remaining floating market in Vietnam’s largest delta.

According to the Cai Rang District People’s Committee, about 200 boats are now operating regularly in the market, a sharp decline from the 500 operating there in 2016. The most significant drop happened during the construction of the Can Tho river embankment project.

In other floating markets like Nga Nam and Nga Bay, the number of regularly operating boats has dwindled to fewer than 10. Occasionally, only a few tourist boats are seen taking visitors along the river.

Yet during the early 1990s, the Nga Bay Floating Market saw up to 800 vendor’s boats daily, according to Nham Hung, a researcher of Mekong Delta culture.

The market once spread out over nearly half the river, covering more than one kilometer along seven tributaries, and stretched over an estimated 500-700 hectares of water.

Such vibrance now exists only in the memories of a few residents.

“When I was young, the market was incredibly crowded and boats were moored so close together you could walk from one side of the river to the other,” recalled Oanh.

“It was easy to make money back then. During the day, we sold fruit, and at night, we sold desserts, noodle soup and sticky rice,” Oanh said.

At 17, Oanh would transport 500-600 kilograms of fruit by herself from Nga Bay to sell in Soc Trang province.

“Back then, business was easy and with good health, I was eager to work,” she recalled. “Every week, I could save up to one tael of gold (about 37.5 grams, or 1.2 troy ounces). Just selling fruit from one mango tree could earn me up to 6 taels of gold. Now, I can’t even earn one tael in a whole month.”

The impacts of infrastructure

In 2002, the Nga Bay Floating Market was relocated 3km from its original site due to environmental risks. Areas where multiple river branches converge often experienced whirlpools and widespread congestion from moored vessels.

Additionally, during the flooding season, strong currents could cause accidents, such as boat collisions and sinkings.

Since then, the market has become increasingly desolate.

According to residents, one reason leading to Bay’s decline is the development of road transport. For example, newly constructed roads leading to Bac Lieu, Phung Hiep and Ca Mau provinces have led many to choose the convenience of trucks over boats.

Additionally, the construction of embankments around the market has directly contributed to its decline.

“The embankments prevent erosion and are pleasant-looking, but traders have no place to dock,” explained a local food vendor who wished to remain anonymous.

The same fate has befallen many other floating markets in the Mekong Delta as road transport becomes more prevalent. In a meeting last year with the Cai Be District People’s Committee, officials showed that the number of boats operating in traditional floating markets has sharply declined.

Traders now negotiate prices directly with farmers and use land transport, making it harder for floating market vendors, many of whom have switched professions.

Inconsistent income from agricultural sales, due to price pressures from middlemen and a lack of outlets, has also led to fewer vendors.

At the Cai Rang Floating Market, one of the last remaining in the region, business is slow. Bay, a noodle seller, used to sell up to 120 bowls a day, reaching over 150 at peak times, mainly to traders. However, since Covid-19, she now sells about 50 bowls daily.

“A lot of big boats used to come here to trade, and you couldn’t see the water,” she recalled.

A director of a large resort in Can Tho with over 20 years of experience in floating market tourism, who wished to speak anonymously, said the region used to rely on boats to transport produce, creating a strong market demand. Now, with rural transport improved and trucks able to directly access farms, the floating market’s role has diminished.

The construction of embankments has further impacted boat traffic, making it difficult for traders to load and unload goods.

“If Cai Rang Floating Market disappears, we don’t know how tourism will continue,” she said.

For those living and trading at Cai Rang, their livelihoods are at risk if the market vanishes. Bay, despite having a house built with compensation from the embankment project, depends entirely on the market.

“I’ll keep selling from my boat until I’m too weak to continue. I’m used to it. I can’t manage on land,” she admitted.

Similarly, Dang Thi Dieu, who has lived and traded at Cai Rang for more than two decades, struggled to find alternative livelihoods. Having moved from Phong Dien to the bustling market years ago, she now feels lost if she returns to her hometown.

“I don’t know what to do back home – I’m so used to trading,” she said. With no stable income, her eldest daughter had to stop her education after high school to help support the family.

Precarious future

At the Nga Bay Floating Market, ongoing clearance and compensation efforts for the embankment project are threatening local livelihoods once again.

Duyen from Nga Bay noted that after the market’s closure, she and her husband shifted to making traditional baskets. However, orders have dwindled since Covid-19.

“I make 10-12 baskets a day, earning VND11,000 (about USD0.44) each,” she said. Although they received compensation and moved to a better resettlement area, Duyen and others fear their future is bleak.

“They ask for our opinion, but offer no real solutions. Resettlement often means loss of livelihood and opportunities,” she lamented.

Nga Bay City aims to develop tourism as a key economic sector, but has not yet revitalized the floating market. Meanwhile, at Cai Rang Floating Market, improvements on the new pier have been made after complaints about the high embankments hindering boat access.

“Some boats left for Dong Thap province during the embankment construction, but some have recently returned,” said Nguyen Khanh Tung, head of the Can Tho Institute of Socio-Economic Development (CISED).

However, this is only one of many needed solutions to sustain floating markets. Tung explained that while floating markets were once spontaneous, increasing boat numbers and tourism created management challenges. Families long settled at these markets have habits and livelihoods tied to the riverbanks, making relocation difficult and ensuring comparable living conditions is crucial.

Tung added that floating markets’ basic principle involved boats working with shore-based shops, with the latter contributing 70-80 per cent to the boats’ revenue. The embankments disrupt this link, forcing traders to find new locations.

“To preserve Cai Rang Market, we need to ensure suitable locations for both boats and shops,” he suggested. CISED’s draft conservation plan for Cai Rang Floating Market by 2030 includes recommendations based on Thailand’s model, such as investment in warehouses, commercial areas and performance spaces.

However, a resort director in Can Tho argued that current efforts focus too much on cultural aspects and overlooked the crucial need to maintain traders’ livelihoods.

“We need to understand their needs, such as schooling for their children and issues like fuel,” she said.

She proposed a tourism-focused floating market with nearby kiosks for food and souvenirs, allowing tourists to experience traditional markets and local specialties.

The decline of floating markets in Mekong Delta is not only a cultural loss, but a critical economic issue. As these markets fade, many families face job instability, often leading to migration to cities like Ho Chi Minh City or seeking overseas labor opportunities.

For instance, Dieu’s family is considering labor migration to South Korea due to the lack of local opportunities.

“If we can’t find work in the city and costs are high, we may end up borrowing money for overseas work,” Dieu said.