As droughts and saltwater intrusion devastate the Mekong Delta, many women are forced to seek alternative ways to make a living. This new path may offer a glimmer of hope, but it also exposes their extreme vulnerability.

By Kieu Mai

In a sprawling durian orchard next to a small concrete road running through Tien Thuy commune in the southern province of Ben Tre, Tran Thi Chon, a woman in her sixties, carefully sweeps up piles of dry leaves and meticulously inspects the ditches that store fresh water. As the day fades into night, the darkness envelops her, accompanied only by the symphony of insects and rustling leaves, and a faint glimmer of light from her nearby home.

Chon has been worried about her newly replanted durian orchard since the dry season began in late December. Seven years ago, a historic saltwater intrusion wiped out her nearly harvest-ready durian trees and a considerable part of her family's fortune.

Droughts and saltwater intrusion have been wreaking havoc on the Mekong Delta for several years now, forcing many women like Chon to take a different path to earn a living. This has not only opened up new opportunities for these women but also exposed their extreme vulnerability.

Extreme climate

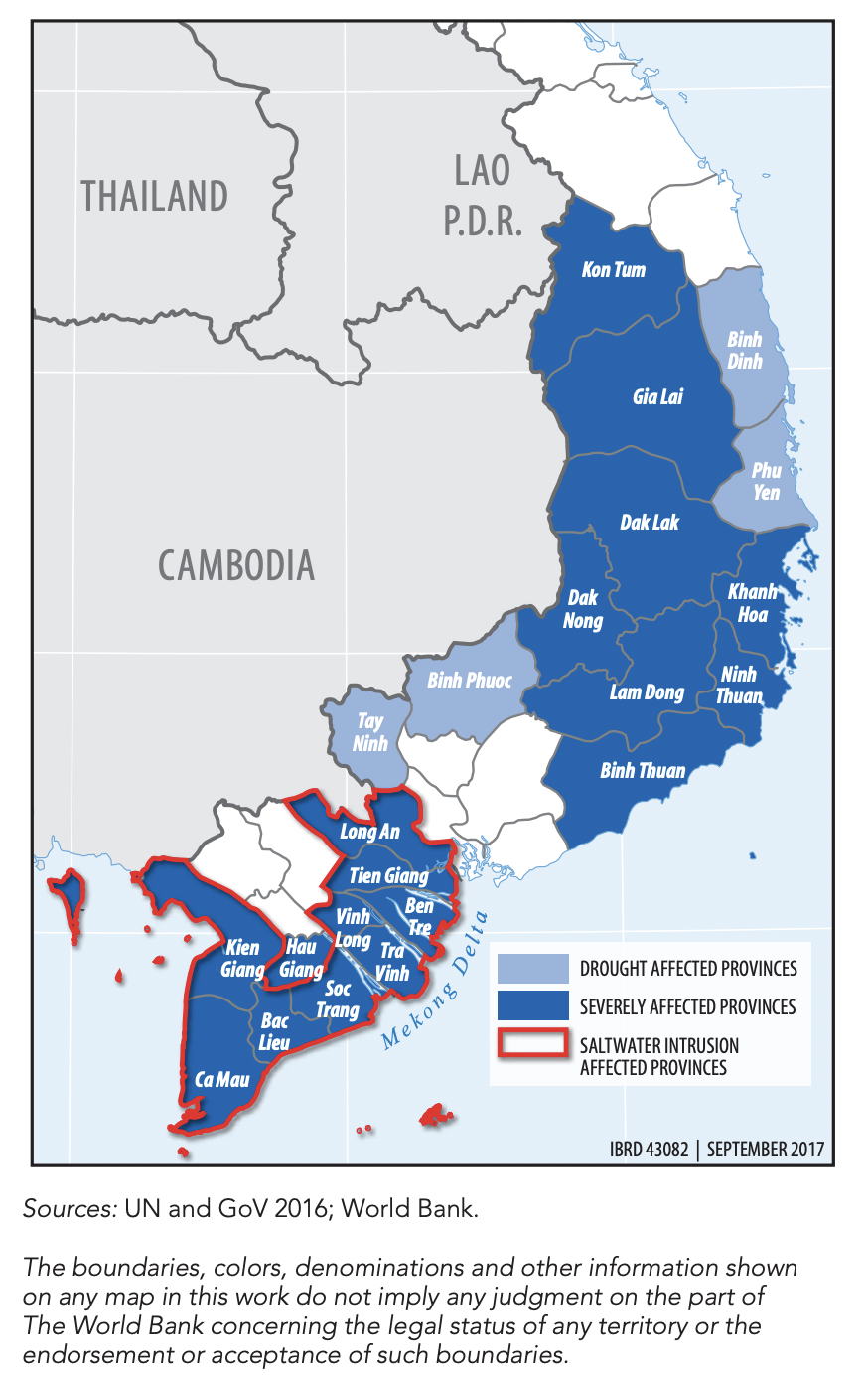

Saltwater intrusion is a natural occurrence in the Mekong Delta. But in 2015 - 2016, it caused significant damage to the area of fruit trees, crops, and aquaculture. According to data from the National Center for Socio-Economic Information and Forecast (NCIF), saline intrusion affected about 40 – 50 percent of rice farming land and up to 69,000 hectares of aquaculture area in the region, accounting for most of the country’s damaged aquaculture area in the period.

It was linked to the longest El Niño in Vietnam’s history, a weather phenomenon that typically causes high temperatures and lower than average rainfall, according to the National Steering Committee for Natural Disaster Prevention and Control.

Saltwater intrusion appeared two months earlier than usual, with the highest range of saline intrusion inland up to more than 90km. The construction of dams upstream on the Mekong River reduced the amount of freshwater flowing into the delta, which made it easier for seawater to penetrate inland, causing increased salinity levels in freshwater resources.

In 2015, Vietnam also suffered its most severe and prolonged drought in 90 years, caused by El Niño and marked by warmer temperatures and extended dry spells, the World Bank reports.

Unfortunately, the extreme weather events have persisted, and in June and July of 2019, the Mekong River levels dropped significantly compared to previous years, heightening fears of drought and saline intrusion throughout the Mekong Delta in the 2019 – 2020 dry season.

Shouldering a double burden

For Chon and many other women in the Mekong Delta's provinces, the aftermath of saltwater intrusion meant an increased workload when the soil is saline for a long time, and a financial burden when traditional incomes are no longer enough to survive.

"Watering a lot only helps to make the top layer of the soil less salty, but deep below it is still very salty,” Chon said. “Replanting trees means cultivating, fertilizing the land again and again, as well as raising the durian mounds higher. The workload is much more than before."

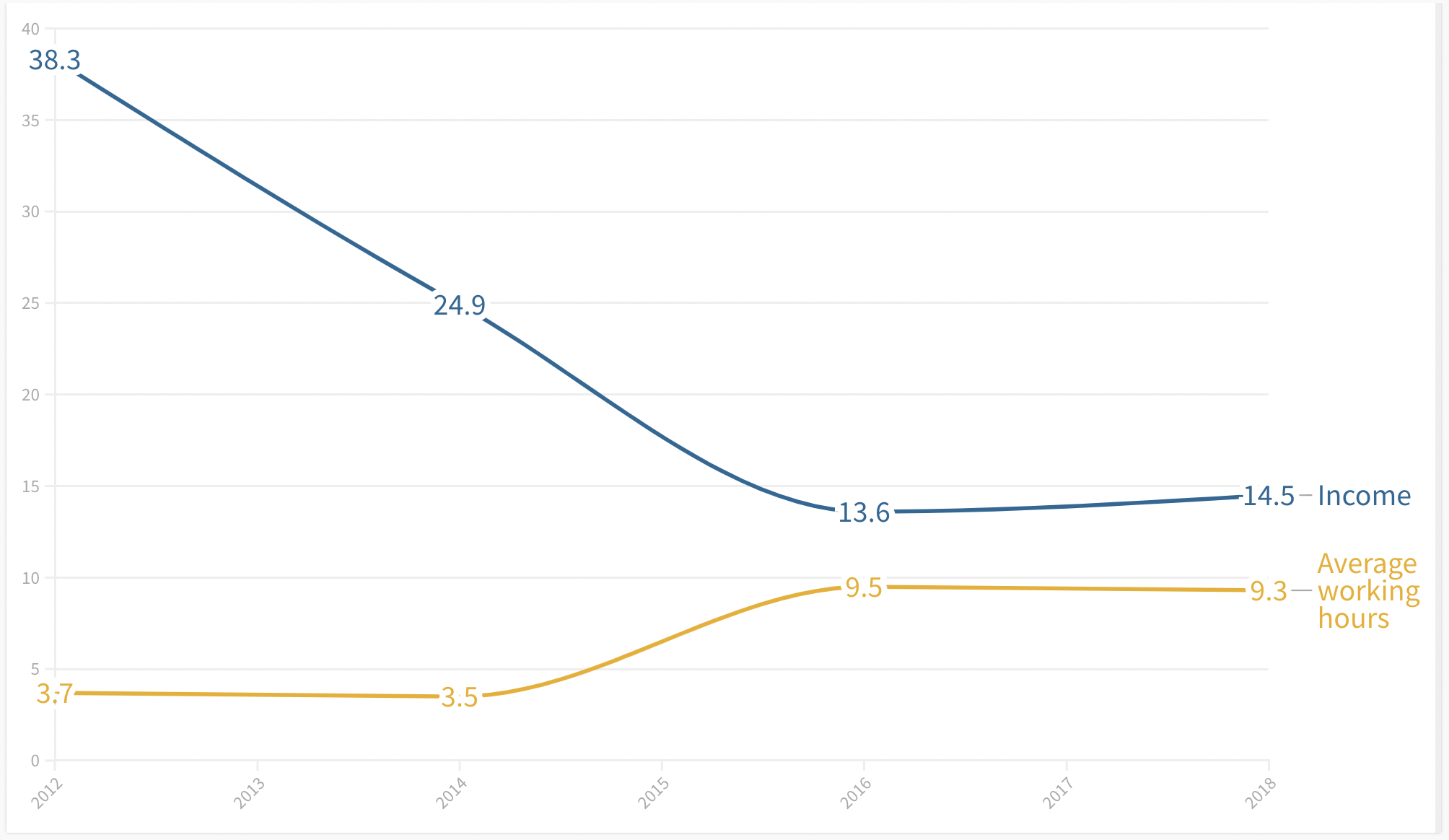

Analysis of data from the NCIF in 2020 shows that severe drought and saltwater intrusion in the Mekong Delta have forced farmers to increase their working hours to supply fresh water for plants and animals, while their income growth rate has decreased. This has reduced the productivity growth rate of farmers, making it more difficult for them to protect their crops and animals from the negative effects of climate change.

According to the UN’s "The State of Gender Equality and Climate Change in Vietnam" report from 2021, climate change-induced water insecurity has increased the burden on women, particularly those involved in small-scale farming, who must allocate more time and energy to land preparation, fetching water, and watering and safeguarding crops against diseases.

After her durian garden perished in 2015, Chon turned to growing kumquats and making wine to make ends meet. But the income from this new venture wasn't enough to sustain the couple, who relied heavily on the orchard for their livelihood.

Determined to find a more secure source of income, Chon and her husband decided to plant durian again, despite the risks. The fruit has the potential to yield up to VND300 million (about $12,600) per thousand square meters per season, a much-needed lifeline for the aging couple. With their health in decline, they were no longer able to pursue higher-paying jobs outside of agriculture.

Stay or leave?

As the impacts of climate change continue to ravage the region, the livelihoods of many families have been put at risk. Women, in particular, have been forced to take on the role of economic breadwinner, often juggling multiple jobs to support their families.

Traditional gender roles in Vietnam dictate that women are responsible for household chores such as cooking and caring for family members. This makes it difficult for them to make career changes. Some opt for seasonal jobs in neighboring provinces to ensure they can still take care of their families. However, this often means accepting more work and hardship.

According to the UN’s 2021 report, men tend to migrate to urban areas for income opportunities when extreme weather events create fluctuations in agricultural production. But most women remain in the countryside, especially older women and those with infants who don't have the opportunity to leave their homes.

Nguyen Thi Kim Thoa, founder of Abavina, a pioneer enterprise in community-supported agriculture in Can Tho city, notes that men tend to change jobs more easily than women. This is because most men often get higher-paying jobs and are not responsible for family care.

"Women in the Mekong Delta have to rely heavily on outside support, and are more affected by the decline in income in agriculture," Thoa said. The decline in agricultural productivity not only affects women's job choices but also leads to a decline in their status and voice in the family, she added.

Barriers to migration

Some women stay in their hometown while others leave to find a better future. Tran Thi Linh (name changed) and her husband moved to Dong Nai province to work when their children were old enough.

Since they couldn’t afford childcare in the city, they had no other choice but to leave their children with the grandparents. They had planned to visit them regularly but their new jobs take up most of their time.

“We know that the children will lack our love and care, and they will have to be independent sooner when living far away from parents,” Linh said. "But we have no choice, because if we only rely on farming, how can we take care of your family when health risks occur? Our grandparents are also old now, we are forced to take care of everything.”

According to a 2019 survey conducted by the Institute of Policy and Strategy for Agriculture and Rural Development (IPSARD), the percentage of female migrants leaving the Mekong Delta for more developed provinces and cities is nearly equal to that of men. Notably, the migration rate of female workers under the age of 35 is particularly high.

As demand for agricultural labor decreases and income from traditional agricultural production dwindles, many rural women in the Mekong Delta are choosing to migrate and join the workforce in more developed areas, IPSARD reports. However, these women face lots of obstacles in their new working environments, including lack of access to social insurance, no on-site childcare facilities, and inadequate medical resources.

IPSARD also notes that traditional beliefs about gender roles in the Mekong Delta often limit women’s participation in skills training and job opportunities that could generate additional income.

Thoa of Abavina, who works with rural women, agrees that these outdated beliefs are limiting the potential of women in the region. She argues that they create an invisible barrier that prevents women from pursuing new opportunities and gaining new knowledge.

To increase the resilience of women in the face of climate change, Thoa believes that short-term support is needed to increase the value of gardens and boost crop productivity through technological advancements. This could include using new plant varieties with greater resistance and installing automatic watering systems to regulate water usage. In addition, Thoa highlights the need for farmers to receive support in designing their gardens in the most efficient and effective manner possible.

Farmers also require support to connect with agricultural product agents and buyers via independent intermediaries or local agencies to boost sales. In Abavina, affiliated stores in Ho Chi Minh City buy fruits and vegetables from farmers in response to clean agricultural product requests, resulting in higher income from quality products.

In the long run, priority should be given to educating women to enhance their awareness and abilities, enabling them to communicate, understand, and accept positive changes with confidence, Thoa said.

"Studying for rural women in the Mekong Delta often does not mean to change lives, but to help them get over their shyness, and then, integrate better into a fast-paced life," she said.

Phung Duc Tung, director of the Mekong Development Research Institute, also emphasizes the importance of improving women's education levels to promote their participation in sustainable and high-income jobs.

As women join the economy and earn higher incomes, their share of power in households will change. While this change can create new pressures and challenges, it might improve the status of women in Vietnamese society.

Whether they choose to stay in their hometowns or migrate in search of work, women in the Mekong Delta like Chon and Linh face significant difficulties and pressures. However, their perseverance in striving for a better future every day is a testament to their resilience in the face of climate change.